Subscribe in a reader

Subscribe in a reader

This

biography, that connects the poet's life with his work, is a welcome

addition to the corpus building around Nichol. It explores the

relationship between Barrie Nichol - the living breathing human

being, as excavated from conversations with friends, relatives,

colleagues, and acquaintances; from letters; and from archives –

and bpNichol, the authorial persona created by Nichol to pull himself

out of the dreamworld he inhabited, according to Davey.

It

forwards the theory that Barrie's psycho-therapeutic work is a

crucial tributary of his poetic work. While I am not qualified to

evaluate this theory (I'm not versed enough in Nichol's poetry,

having read only Zygal and

some excerpts of the Toronto Research Group, bp's theoretical, albeit

playful collaboration with Steve McCaffrey in a course I took with

Christian Bök

at the University of Guelph in 2002), I would still like to offer

some reactions and thoughts.

My

initial reaction to the book was “I think this is the first

biography that has made me less interested in the person it's about

than I was before I picked the book up.” However, I persevered, and

I'm glad I did. Davey is an engaging writer, although his thoughts

are sometimes muddled. For example, take this passage:

“He

[bp] told Bowering he was creating the whole narrative out of a

series of images that would constitute a two-week period in the life

of a family, a period in which, as one would expect, nothing is

resolved. The reader enters and leaves the narrative in the middle,

and 'hopefully' will experience a resolution through the leaving of

it. The images will be all that the reader knows about it. That's why

he's calling the novel 'idiomatic,' he told Bowering, because it's

the normal 'family' story. The explanation, however, seemed to say as

much about Barrie's understanding of family, or about what is usual

in a family, as about the novel” (238).

Um,

what? Seriously, what just happened here? Some of the clarity problem

in this particular instance may have been inherited from Nichol

himself, as he's the one being paraphrased, but if you're writing a

biography, you better have enough of a grip on your subject to

clarify some of the subject's more incoherent thoughts. Nothing is

resolved, but the reader will hopefully experience a resolution? Is

he talking about relating to the aimless structure of life portrayed

by the in media res technique

as itself some kind of resolution? Furthermore, idiomatic is a word

used in linguistics to refer to expressions in language that are

“more than the sum of their parts,” so to speak. Translating each

of the parts of the expression literally will not produce the

intended meaning of the expression. How does this relate to “normal

family experience?” Idioms, I guess, are common expressions. So if

you consider “normal” and “common” synonyms, this metaphor

works. Ok, so with some very close reading, I could figure out that

much. But what Davey means by the next sentence (beginning “The

explanation, however. . . “) needs more elaboration as the logic is

unclear.

Furthermore,

Davey makes a big deal out of Nichol's intent from the 1960s onward

to subvert the arrogance of many poets' preoccupation with precious

(with that word's pejorative connotations culled from writing

workshops) wisdom as the occasion for the writing of poetry. To

express such wisdom, as an author with the mastery of experience,

Nichol objected to stridently, apparently. However, in the sections

detailing Nichol's work at Therafields, the experimental therapeutic

community for which he served as vice-president, and Nichol's

discussions of this work, he adopted the founder's discourse of

mastery. Lea Hindley-Smith, the founder, “had been moved by

Bergler's book to 'change her own destiny rather than blame others'”

(82).This contradiction between his lived experience as a therapist,

proclaiming mastery of experience and himself in a privileged

position to help his clients do the same, and his avowed poetic

intent to eschew such arrogant language, is a thorn in the side of

Davey's poetry-therapy theory.

Furthermore,

some of his poetry contains some of these golden nuggets he finds so

repugnant and arrogant. Take, for example, these lines quoted by

Davey, from “Book V” of The Martyrology Book 6 Books:

moving

reservoirs of cells & genes

stretches

out over the surface of the earth

more

miles than any ancestor ever dreamed

.

. .

tribal,

restless, constant only in the moving on,

over

the continents

thru

what we call our history

tho

it is more mystery than fact,

more

verb than noun,

more

image, finally, than story.

These

lines are redolent of the “preconceived notion of wisdom” bp (and

others such as Charles Olsen) rebelled against in poetry. While it is

true that people certainly change their views as their experience

changes them, it is Davey's job to elucidate this development in

Nichol's poetry. Instead, Davey returns to this youthful rebellion

several times, making it a central point or major departure for his

poetic work. For a dedicated avant- gardist, the first stanza of this

quote in particular has a harmonious sense of meter and rhyme (if

partial, or slant). Most of it is insightful and “wise” as well.

. . until the last line quoted. I find the frozen associations of the

word “image” do an injustice to his previous line about history

being more verb than noun. A photograph, after all, is an image

extracted out of the flow of time. I suppose you could argue that

this line is a subversion of the “preconceived wisdom” of the

poem, but I think it weakens its internal coherence. I also think he

missed an opportunity for a playful self-reflection of the line “tho

it is more mystery than fact” as itself a fact, considering the

always incomplete nature of archives. And by extension, this line and

its implications allude to the challenge of writing a faithful

biography, which by and large Davey has done.

Criticism

aside, I found this book fascinating because of the connection it

explores between Nichol's deep involvement with psychotherapy and his

poetry. It was also edifying to learn about Nichol's peripatetic

childhood, his hermetic “dreamworld,” and his relationships with

other Canadian literary figures. I was familiar with his relationship

with Steve McCaffrey, but his relations with other poets and writers

such as Daphne Marlatt, Michael Ondaatje, Dennis Lee, and bill bisset

came as a surprise and a delight to me.

I

was also surprised at how high-profile his sound poetry projects

were, such as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. For a

Nicholophile, to learn about how he felt like his creative input was

constantly marginalized in that project is a must. The last chapter

provides a useful summary of some of the main critical responses to

Nichol's work: the “theological reception,” those that emphasize

his “ideopoems” that merge comic strip art with conceptual visual

poetry, and those that focus on The Martyrology

as the keystone of his creative output. This summary is indispensible

for those interested in a critical engagement with Nichol's work.

Despite its shortcomings, Davey's biography was well worth the time.

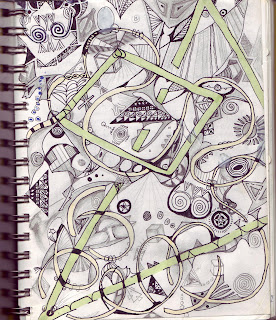

Images from Zygal (1985), Coach House Press.