All material on this blog has been copyrighted. Use any materials therein without permission and risk civil liability as applicable under your countries copyright laws.

Share this

Wednesday, May 06, 2020

Friday, December 08, 2017

The sound of aggregate activity

Breezy in the late, stabbingly bright

blue

Of an afternoon

Soft yellows caress

The late-out-of-the gate lilacs

Smelling sensual, lurid.

What rest can be got from this swirl

Of smells overpowering

Malefactors everywhere

Actors and blinks, nods, and who’s

hooligans.

Read them the Cactus riot act.

She flowers every seven years

Or if the new moon follows on the

first

Friday after Easter infection,

Then, only then, will she spread her.

. . petals

It was in a photograph, or –gram

Heavy metal pelt stain melt brain;

ham radio

Operator; one caught in the

electricity

Wires.

I saw him on my walk home from world.

Singing ‘ole glory to the world,

A face turned murderous

As if a cloud smirched the soulful

sky.

In the corner of the photograph,

A figure in sticks, wrapped in the

dangerous

Sourcery of the exorcism,

Darkness swirling off him in colour

grids

Dextrous fingers of the toppling

dominoes

In the foreground, under the table,

Barely visible.

Flim flam, hone it for the street

corners.

In the hides of summer, wearing

Sun’s great glory on the

sweat-sheened skin

We can write about life,

Or we can write about life.

Precipitating the “oh, not the ‘we’

shit again.”

II

The happiness of a single fuck not

given

The apathy trickle-down vectors

Swerving high on unpredictable

Ever veritably new, improved

Dazzling desuetude.

III

Suet in a fur-trap.

A straw, balanced on a camel’s back,

Photographed.

For a response to a query

Responded to and refuted

From every corner of the

crypto-verse.

The cacti, in a row, made a fence

To keep the cattle in,

Some do it,

Some don’t.

IV

The next time she appeared,

A blue streak ran rampant around

The orbituaries climbing out of the

newsstands.

Surprise factor, attention disperser.

Social facts uncalled upon.

This is poetry’s rent.

Tantamount to a slope of fine

powdered salt

To cushion our 20 feet jumps

Down a steep incline.

Don’t think too much

Or you will start to smell the

cowpaste

Piling up in the meadow.

Piling up in the meadow.

Monday, December 29, 2014

A Review of Frank Davey's Biography of bpNichol (2012), by Trevor Cunnington

This

biography, that connects the poet's life with his work, is a welcome

addition to the corpus building around Nichol. It explores the

relationship between Barrie Nichol - the living breathing human

being, as excavated from conversations with friends, relatives,

colleagues, and acquaintances; from letters; and from archives –

and bpNichol, the authorial persona created by Nichol to pull himself

out of the dreamworld he inhabited, according to Davey.

It

forwards the theory that Barrie's psycho-therapeutic work is a

crucial tributary of his poetic work. While I am not qualified to

evaluate this theory (I'm not versed enough in Nichol's poetry,

having read only Zygal and

some excerpts of the Toronto Research Group, bp's theoretical, albeit

playful collaboration with Steve McCaffrey in a course I took with

Christian Bök

at the University of Guelph in 2002), I would still like to offer

some reactions and thoughts.

My

initial reaction to the book was “I think this is the first

biography that has made me less interested in the person it's about

than I was before I picked the book up.” However, I persevered, and

I'm glad I did. Davey is an engaging writer, although his thoughts

are sometimes muddled. For example, take this passage:

“He

[bp] told Bowering he was creating the whole narrative out of a

series of images that would constitute a two-week period in the life

of a family, a period in which, as one would expect, nothing is

resolved. The reader enters and leaves the narrative in the middle,

and 'hopefully' will experience a resolution through the leaving of

it. The images will be all that the reader knows about it. That's why

he's calling the novel 'idiomatic,' he told Bowering, because it's

the normal 'family' story. The explanation, however, seemed to say as

much about Barrie's understanding of family, or about what is usual

in a family, as about the novel” (238).

Um,

what? Seriously, what just happened here? Some of the clarity problem

in this particular instance may have been inherited from Nichol

himself, as he's the one being paraphrased, but if you're writing a

biography, you better have enough of a grip on your subject to

clarify some of the subject's more incoherent thoughts. Nothing is

resolved, but the reader will hopefully experience a resolution? Is

he talking about relating to the aimless structure of life portrayed

by the in media res technique

as itself some kind of resolution? Furthermore, idiomatic is a word

used in linguistics to refer to expressions in language that are

“more than the sum of their parts,” so to speak. Translating each

of the parts of the expression literally will not produce the

intended meaning of the expression. How does this relate to “normal

family experience?” Idioms, I guess, are common expressions. So if

you consider “normal” and “common” synonyms, this metaphor

works. Ok, so with some very close reading, I could figure out that

much. But what Davey means by the next sentence (beginning “The

explanation, however. . . “) needs more elaboration as the logic is

unclear.

Furthermore,

Davey makes a big deal out of Nichol's intent from the 1960s onward

to subvert the arrogance of many poets' preoccupation with precious

(with that word's pejorative connotations culled from writing

workshops) wisdom as the occasion for the writing of poetry. To

express such wisdom, as an author with the mastery of experience,

Nichol objected to stridently, apparently. However, in the sections

detailing Nichol's work at Therafields, the experimental therapeutic

community for which he served as vice-president, and Nichol's

discussions of this work, he adopted the founder's discourse of

mastery. Lea Hindley-Smith, the founder, “had been moved by

Bergler's book to 'change her own destiny rather than blame others'”

(82).This contradiction between his lived experience as a therapist,

proclaiming mastery of experience and himself in a privileged

position to help his clients do the same, and his avowed poetic

intent to eschew such arrogant language, is a thorn in the side of

Davey's poetry-therapy theory.

Furthermore,

some of his poetry contains some of these golden nuggets he finds so

repugnant and arrogant. Take, for example, these lines quoted by

Davey, from “Book V” of The Martyrology Book 6 Books:

moving

reservoirs of cells & genes

stretches

out over the surface of the earth

more

miles than any ancestor ever dreamed

.

. .

tribal,

restless, constant only in the moving on,

over

the continents

thru

what we call our history

tho

it is more mystery than fact,

more

verb than noun,

more

image, finally, than story.

Criticism

aside, I found this book fascinating because of the connection it

explores between Nichol's deep involvement with psychotherapy and his

poetry. It was also edifying to learn about Nichol's peripatetic

childhood, his hermetic “dreamworld,” and his relationships with

other Canadian literary figures. I was familiar with his relationship

with Steve McCaffrey, but his relations with other poets and writers

such as Daphne Marlatt, Michael Ondaatje, Dennis Lee, and bill bisset

came as a surprise and a delight to me.

I

was also surprised at how high-profile his sound poetry projects

were, such as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. For a

Nicholophile, to learn about how he felt like his creative input was

constantly marginalized in that project is a must. The last chapter

provides a useful summary of some of the main critical responses to

Nichol's work: the “theological reception,” those that emphasize

his “ideopoems” that merge comic strip art with conceptual visual

poetry, and those that focus on The Martyrology

as the keystone of his creative output. This summary is indispensible

for those interested in a critical engagement with Nichol's work.

Despite its shortcomings, Davey's biography was well worth the time.

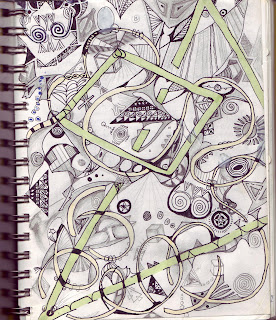

Images from Zygal (1985), Coach House Press.

Tuesday, December 09, 2014

An Ecclesiastical View on Visual Culture (if you will excuse the pun)

So it's been a while since I posted anything. If any of you are disappointed, I apologize. Sometimes the lemonade that life throws you can't be turned into lemons. Anyhow: busy is busy. Here's something I wrote in 2009 about the "new" academic field of Visual Culture. Trigger warning: academic language ahead.

The

Insufficiency of Linguistics in the Age of the Machine

Visual

Culture is a discipline that tries to put in a comprehensible

framework images, which are visual data that have been interpreted,

endured in memory, become represented, and have accrued significance

in the processes of interpretation, remembrance, and representation.

It is somewhat analogous to Saussure’s seminal work on linguistics,

but rather than focus on language as

language, it analogically expands analysis of the structure of the

communicable into the field of images, and their manipulation through

techniques and technologies of seeing and looking. As culture is a

way of life, as well as shorthand for organized and intentional

sensual experience in the form of various arts, Visual Culture’s

object is how visual data inform the practice of culture. How do

configurations of visual data cohere as signs through structures of

meaning? What kind of strategies do encoders use to enframe

interpretation and to what ends? What strategies do decoders use to

interpret, with what motivations, and to produce what results?

On

the other hand, an image is fully communicable in language. Ezra

Pound’s poem “In the Station of the Metro” or William Carlos

William’s poem “The Codhead” are proof positive of this.

Furthermore, in literate society the visuality of language

irrevocably changes its use, as scholars from Eisenstein, Havelock,

and Ong to Innis and McLuhan have noted. In Visual Culture, then,

the problem emerges of the insufficiency of linguistics to

interrogate visual data and its tendency to collect significance like

a magnet collects iron filings. This metaphor is apt both because a

sign, a certain distillation of sensory – in this case visual –

data, starts off as many disparate parts, but in the process of

encoding or decoding it joins parts into a whole, a whole which is

greater than simply the sum of its parts. The magnet is

consciousness. The extrapolation of linguistic concepts into a wider

field of sign production, observation, and interpretation, such as

that accomplished by Barthes, is the essential act of Visual Culture,

and it is predicated on the irreconcilable hybridity of human, machine,

and perception.

Is

Visual Culture new, emergent,

or any of the other modifiers that reveal the coy

imbrications of academia with the market (new and improved!)? Emphatically no. The

political cartoonist extraordinaire

of enlightenment England, Cruikshank, in the process of observing

politics and culture through various degrees of mediation – which

necessarily implies representation – must have employed some of

the same strategies, or at least trod in similar cognitive footsteps,

as contemporary cultural critics have in their analyses in order to

draw his cartoons in the first place. One must interpret visual

aspects of culture at large in order to consolidate visual data and

subsequently encode such a complex but simple-seeming formulation as

a cartoon.

For example, in this cartoon, Cruikshank depicts people from various classes working together to export orphans to the colonies. In the nineteenth century, children were not guaranteed the same rights as they are now. Corporal punishment was the norm, and orphaned children were a social problem that warranted, to some, an easily solution: ship them out to the far reaches of the empire. It was common practise also to ship unwedded and pregnant women to the colonies in the interests of "social hygiene." With a nod to Jonathan Swift's satirical essay "A Modest Proposal," Cruikshank here lambastes the practise as dehumanizing. The top hat and erect stance of the man in the centre emblemizes "polite society," that of refined gentlemen. The other man's stance, slightly stooped, and his raggedy bowler testify that he belongs to the working classes. A woman, in the background, also pitches in. This cartoon shows the co-operation of different social groups, often in conflict in other arenas, all working together to rid their society of a group beneath them all -- unwanted children. The tension between the emblems of civilization and an obviously barbaric act -- shoveling children into a cart -- shows the active nature of Cruikshank's "reading" of his visual environment, and then redeploying its parts for persuasive purposes.

With regards to "newness," I usually side with the author of Ecclesiastes, who laments “there is nothing new under the sun.” To claim there is something new is at the same time to claim complete and total knowledge, an act of arrogance, and further, of ignorance of one's own ignorance. However, the pixilated milieu of contemporary existence, especially with regards to communication, has made it such that these liminally conscious processes should be brought into the foreground and conceptualized, following Marcuse’s notion that the image and its superabundance militates against conceptual thinking.

For example, in this cartoon, Cruikshank depicts people from various classes working together to export orphans to the colonies. In the nineteenth century, children were not guaranteed the same rights as they are now. Corporal punishment was the norm, and orphaned children were a social problem that warranted, to some, an easily solution: ship them out to the far reaches of the empire. It was common practise also to ship unwedded and pregnant women to the colonies in the interests of "social hygiene." With a nod to Jonathan Swift's satirical essay "A Modest Proposal," Cruikshank here lambastes the practise as dehumanizing. The top hat and erect stance of the man in the centre emblemizes "polite society," that of refined gentlemen. The other man's stance, slightly stooped, and his raggedy bowler testify that he belongs to the working classes. A woman, in the background, also pitches in. This cartoon shows the co-operation of different social groups, often in conflict in other arenas, all working together to rid their society of a group beneath them all -- unwanted children. The tension between the emblems of civilization and an obviously barbaric act -- shoveling children into a cart -- shows the active nature of Cruikshank's "reading" of his visual environment, and then redeploying its parts for persuasive purposes.

With regards to "newness," I usually side with the author of Ecclesiastes, who laments “there is nothing new under the sun.” To claim there is something new is at the same time to claim complete and total knowledge, an act of arrogance, and further, of ignorance of one's own ignorance. However, the pixilated milieu of contemporary existence, especially with regards to communication, has made it such that these liminally conscious processes should be brought into the foreground and conceptualized, following Marcuse’s notion that the image and its superabundance militates against conceptual thinking.

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Letter from Tom Thomson to the world

I have found enlightenment.

My body was never found

Because I absconded

To the muskeg

Further north

North further than the last

road.

I am not rotting in the muck

In tea lake.

Ironically, perhaps,

enlightenment

Lurks in places

Unlit.

Thoreau is here,

We discuss

Our proud sons,

Lawrence Harris and Mahatma

Ghandi.

If you wonder

How I got this letter

Through, if my

Situation is as I say;

Suffice it to remark

That here we don’t

Need any radio, laser,

Telegraph, phone,

Smoke signal,

Or even seanceer.

We live in your minds,

Which wrote this.

Monday, September 02, 2013

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Fruitvale Station Review by Trevor Cunnington

Fruitvale Station is a special film that does almost all the right things. I find my thoughts returning to the film quite often in the week since I’ve seen it. It takes a familiar narrative, adds a few surprises, bucks the mold of emotional evocation in film, does some daring things, some plain things, and some innovative things all with panache. It acquires a particularly intense gravitas because of its roots in real events in recent history. I saw it in Toronto, in a less than half-full, smallish theatre, and I hope it was less than half-full because it has been running for a while. This hope is particularly strong because of the resonance between Oscar Grant’s murder by the BART police and the recent murder of Sammy Yatim on a street-car in Toronto. Where is the word of mouth momentum?

The familiar narrative is that of the struggling young black man in urban America, and the difficulty of escaping the ghetto. It takes as its point of departure a cell phone video of the real life event of Oscar Grant having his head slammed into the concrete of the Fruitvale transit station in Oakland, California, and then being shot by BART police officers. Thus, it does a daring thing, narratively speaking – it shows the end of the story first. Not only that, but the footage is so jarringly authentic, I must admit it made me feel a little nauseous. (The advantage of this approach is that the film can’t be “spoiled”). Then, it rewinds to the day leading up to this event, and we follow Oscar trying in difficult circumstances to be a better person. Difficult circumstance #1 is he cheated on his girlfriend, with whom he has a young daughter. Difficult circumstance #2 is he has been fired from his job at a grocery store for lateness. Difficult circumstance #3, we find out later, is a troubled relationship with his mother that he tries to mend by taking on responsibility for the success of her birthday party on December 31, 2008.

After a terse interchange about his activities for the day with his girlfriend, he heads out to the grocery store where he used to work to try to get his job back. One of the innovative things about the film is the blending of onscreen action with a second screen: that of his cell phone as he texts and dials various people. Thus, it tries to deal with the opacity of phone interactions in real life to offer a more internal glimpse of Oscar’s life to great effect. The sequence in the grocery store is marvellously executed. He gets his friend to get him some high-quality crab for his grandma’s famous gumbo, and notices a young white girl struggling to make a decision for a type of fish for a fish fry. After some slick signals with his friend, he lets her know he works there, but is on his day off. Then he calls his grandmother, a master traditional cook, to instruct the young woman. The meaning of this scene is lent some interesting ambiguity by the context of his conversation with his girlfriend in the second scene of the film about cheating and the context of his visit to the grocery store. Being that we don’t know a whole lot about the character yet (except that he has the characteristically fatherly tendency to curry favour with children out of the disciplinary reach of the mother), he could either be trying to pick up this young woman, or he could be trying to go the extra mile in customer service to get his job back. When we learn more about his character, the latter becomes the more likely interpretation.

After this exchange, he tracks down the store manager to beg for his job back. The manager refuses, and we see Oscar has a temper as his voice escalates in anger. The sound editing of this part is masterful, with very subtle ominous tones accompanying his raising voice. As a tactic of persuasion, he asks rhetorically and heatedly if the manager wants him selling dope again (marijuana). This makes no difference, as the manager has already hired someone else. Then we see Oscar driving around in his car, alternately listening to music, and making plans on the phone. One of the plans is his mother’s birthday party, so he speaks both to her and his sister, who can’t make it because she’s working (probably a low-paying job). His mother chastises him for talking on the phone and driving, so he jury-rigs his phone under his skully hat so that he has both hands on the wheel, then he pulls over, showing how he is trying to be more responsible. He’s 22, and we can grant him some slack on this front. He also makes a phone call to a drug buyer to make an appointment.

It is on the rocks (the visual symbolism is telling) of the waterfront that he has a memory, narrated via flashback. The memory is of the year before, when he was in prison for his mother’s birthday, probably for dealing marijuana. His mother visits him, and they discuss his girlfriend and his daughter, from whom they’ve kept his incarceration secret. During their terse conversation, which begins with his mother asking about a welt on his face, a leering inmate makes a stray comment directed at Oscar, and Oscar explodes in anger. Presumably, this is the man responsible for the welt. After this explosion, Oscar’s mother implores him to calm down, and then tells him she will not visit him any more. He then erupts again and is restrained by prison guards, but it is not in anger this time, but despair, as he repeatedly yells an apology to his mother as she walks away in the foreground. This scene likewise has great sound editing, with the same ominous tones accompanying his outburst. We can see the absolute no win situation he’s in: if he doesn’t put on his tough front, he’s liable to suffer consequences later, but by putting on the tough front, his mother’s regard for him suffers.

After this memory, we see him take the bag of marijuana, and empty it over the rocks and the water. When his buyer shows up, he hands him a small packet for free and apologizes by saying he already sold the pot. The buyer rolls up and smokes, and then he goes to pick up his girlfriend from work and his daughter from the day care. His girlfriend verbally heckles him for smoking pot in the car before picking up his daughter, and he doesn’t bother to correct her. We realize later that he is probably mulling over what to tell her regarding his lost job. When they pick up their daughter Tatiana, we see him race her to the car, and this scene is tastefully rendered in slow motion with the sun in the background helping to signify the great relationship he has with his daughter.

Later, as they plan to go out to the city to celebrate the new year, he suggests staying in. She presses. A sequence of his mother’s birthday party is likewise well rendered with overlapping dialogue and a nice touch of domestic realism. His mother urges him to take the BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) instead of drive to San Francisco so they don’t have to worry about being sober to drive. All good advice that ends in catastrophe, with all the tragic implications that the girlfriend and mother must bear afterwards. The train gets delayed, so they are stuck on it when the new year turns. But, never fear! Someone has speakers and an mp3 player, and the subway car erupts in a party. Then, to return to the familiar narrative, Oscar’s prison past catches up to him when the man who threatened him during the conversation with his mother recognizes his name when the woman whom he helped at the grocery store sees him and calls his name. In this moment, his troubled past catches up to him and erupts in violence. The BART police are alerted, and the tense events leading up to the shooting are well-acted on all parts. My favourite thing about this film is the editing in the last few minutes. While Oscar is in critical condition in the hospital, having been shot in his back, the bullet piercing his lung and causing massive internal bleeding, we see a shot of him and his daughter Tatiana, speaking lovingly with each other. Unlike most films, which use music manipulatively in moments like these to evoke emotions, Ryan Coogler chooses to leave this segment totally silent. The result is heart-rending. The last two shots are absolutely gut wrenching, as the director includes in the final shot footage of a shy, downcast real-life Tatiana attending the anniversary of her father’s death. Thus, the film is bracketed by amateur video shots to lend its story an extremely endearing authenticity. This is the only film in the last six years I’ve been to that I’ve heard people audibly sniffling at the end.

For my theory nerds, this film is a great example of Benjaminian historiography; it does important work of salvaging history from the distorted view of the victors by telling it from the perspective of the people who get squashed in its imposing march. It is aesthetically wonderful: it doesn’t shy away from metaphor and symbolism to add heft to the story it tells and it is also daring and innovative. For me, it is a close call between this and The Hunt (Jagten) for best films of the year. Indeed for these two films and The Place Beyond The Pines alone, it has been a great year for film.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)